Originally printed in the September 2018 issue of Produce Business.

Heartland cities retain roots in nearby farms.

As St. Louis grew from a western outpost to a bustling city in the Civil War era, most of the fruits and vegetables eaten by residents made their way into town by way of the Mississippi River.

As St. Louis grew from a western outpost to a bustling city in the Civil War era, most of the fruits and vegetables eaten by residents made their way into town by way of the Mississippi River.

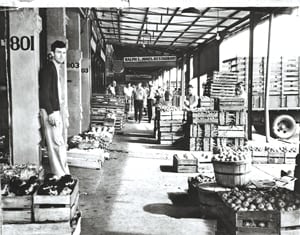

Wholesalers in the area set up shop right on the river, and the first wholesale market developed on Wharf Street on the banks of ‘The Big Muddy.’

Although boats largely have been replaced by thousands of tractor trailers that deliver produce from 49 states and more than 76 foreign countries every day to more than 25 companies that occupy 98 units within the market, the St. Louis Market on Produce Row is still just a few blocks removed from its original site on the Mississippi.

“The river is just a couple blocks away, but we don’t get anything by ship or by train really,” says Sean Kelley, market manager at the St. Louis Produce Market for the past five years. “It’s 99 percent by truck.”

The Sprawling Metropolis

The population served by this complex of coolers and warehouses near the banks of the Mississippi River is no longer a city of 150,000 but a sprawling metropolis of cities, suburbs and towns with 30 times that number of residents.

The population served by this complex of coolers and warehouses near the banks of the Mississippi River is no longer a city of 150,000 but a sprawling metropolis of cities, suburbs and towns with 30 times that number of residents.

“The market operators provide produce for an area 350 miles around St. Louis to 4.5 million people, servicing supermarkets, restaurants, hospitals, hotels, schools, nursing homes, convenience stores, farmers’ markets and roadside produce stands,” according to the St. Louis Produce Market website.

As urban centers in the heart of the nation’s breadbasket, Missouri’s two major cities — St. Louis and Kansas City — probably value the products of nearby farms even more than many larger coastal cities.

“The emphasis on local produce is important when the Missouri and Illinois product is happening,” says Kelley.

On the other side of the state in Kansas City, C&C Produce is a major distributor of produce from some of the largest grower-shippers in the country, including bananas from Dole, leafy greens from Tanimura & Antle, citrus from Sunkist and apples from Sage Fruit.

“We continue to grow in both retail and foodservice,” says Nick Conforti, vice president at C&C Produce, Kansas City, MO. “We go to the big warehouses like Kroger, Associated Grocers, Target and SuperValu, but we also go to the independents.”

Although the company is a source for brand name produce, C&C also has found a welcoming, and growing, market for fruits and vegetables grown close to its heartland home.

“We have a full-time staff person who puts the locally grown program together for people,” says Conforti. “We started the full time guy six years ago, and we went from about $1 million to more than $5 million last year, so it was a good investment.”

As a regional hub serving millions of people in the city and countless nearby small towns, the St. Louis Produce Market has grown from its frontier origins into a large, modern business.

“A government survey shows Produce Row is a $100 million business,” according to the Produce Market website. “It employs 1,200 people, requires 350 trucks, while 1,500 buyers a day come to the Market from the north by Iowa, on the west by Jefferson City and Columbia, on the south by Cape Girardeau and the east by Indianapolis.”

Adapting And Thriving

Although retail consolidation and the emergence of corporate supermarket distribution centers have impacted Missouri, many produce distributors have adapted and continued to thrive.

Although retail consolidation and the emergence of corporate supermarket distribution centers have impacted Missouri, many produce distributors have adapted and continued to thrive.

“We probably lost some business to the distribution centers, but we picked up other business,” says Kelley. “One of the largest grocery stores has a couple units, and there are also businesses that serve the small markets that buy here. We have them all coming here – large markets, independents, restaurants and institutions. The market is healthy; it’s definitely healthy.”

Some wholesalers at the Produce Market have developed important roles by supplying a specific family of crops.

“We’re going after what we do best,” says Daniel Pupillo, Jr., third generation of the family-owned Midwest Best Produce, St. Louis. “Our strong suit is in melons — watermelon, cantaloupe — and pineapple. We bring it in from coast to coast and from Mexico. We’re selling more to retail. The large market chains are looking for deals and service. We used to be more of a combination of both wholesale and retail.”

Although he has found a role in the new world of large corporate retailers, Pupillo notices the change in the dynamics of St. Louis produce.

“Consolidation of retailers has made us more competitive,” he says. “We’ve been able to establish relationships with the retailers through service, but it’s eating up the moms-and-pops. What’s changed is the competition. The margins have tightened up as established and new stores have tried to come in, and it’s made it tough. It’s a competitive town.”

This wholesale market also has evolved to include firms that do repacks, private label and fresh-cut right on site.

“For some of our businesses, fresh-cut has become popular, and packaging has also become popular,” says Kelley. “Our two largest companies at the market do both of those. The organic produce has become popular, too.”

United Fruit and Produce Company has been a leading family-owned-and-operated St. Louis produce business for nearly a century and still headquarters a fleet of trucks serving the region in St. Louis.

A decade ago, the company invested in a state-of-the-art, fresh-cut facility that supplies 140 standard pack items and also offers fruits and vegetables cut-to-order.

Although the company ships and picks up from virtually every major produce hub in the country, United maintains its headquarters in St. Louis’ historic Produce Row district.

C&C Produce also has developed the capacity to offer a range of products from its 200,000-square-foot Kansas City facility with 10 coolers that can each be maintained at different temperatures, a ripening room and facilities to produce fresh-cut.

“We are proud that we are a one-stop shop with fresh-cut, repack, ripening rooms and 10 coolers,” says Conforti. “We fill niches for people.”

Like most cities in agricultural areas, a myriad of small towns that are few and far apart surround St. Louis, and Cusumano & Sons built a business serving these communities.

The company began after Sicilian immigrant Joe Cusumano accumulated enough cash, selling over-ripe bananas from a pushcart on the streets of New York at the beginning of the 20th century, to open a fruit wholesaling operation in St. Louis.

In the 1920s, Cusumano opened a second enterprise 80 miles east of St. Louis — Mt. Vernon Distributing Co., on that small Illinois town’s Main Street.

The family has since moved the Mt. Vernon facility to another location in town, with convenient rail access on both sides of the building, and wholesales fruits and vegetables to nearby retailers.

But in the age of the Food Network and internet bloggers, many of the produce trends in medium-sized heartland cities like Kansas City and St. Louis are much the same as in the largest coastal urban centers.

“We are in the kale and blueberry generation right now,” says Conforti. “I’ve been in the business here for 25 years, and there’s always a newest, hot thing.”

The kale generation wants healthy produce and wants it ready to eat with an absolute minimum of preparation.

“If there’s one big overall change it’s that people want convenience,” says Conforti. “We went from naked lettuce, to cello wrapped, to bagged salads. People don’t want to cut up their own cantaloupe or pineapple anymore.”

Complex Demographics

The City of St. Louis saw its population slowly decline between 2010 and 2016, from just short of 320,000 to a little more than 310,000, according to U.S. Census statistics. Nearly half the city’s residents are black, more than 40 percent white, with more than a quarter of the population living below the poverty line.

The City of St. Louis saw its population slowly decline between 2010 and 2016, from just short of 320,000 to a little more than 310,000, according to U.S. Census statistics. Nearly half the city’s residents are black, more than 40 percent white, with more than a quarter of the population living below the poverty line.

In the greater St. Louis metropolitan area three-fourths of the 2.8 million people are white, and a little less than 20 percent are black.

In the City of Kansas City, which is 55 percent white, 30 percent black and 10 percent Hispanic, the poverty rate is a little more than 16 percent.

The 2.1 million residents of the Kansas City metro area are more than 77 percent white, a little more than 12 percent black, and 8 percent Hispanic, with around 10 percent living below the poverty line.

While a quarter of the five million residents of the two metropolitan areas are black, Hispanic or Asian, there is not a significant sector of produce retailers catering to specific ethnic groups in the St. Louis area, as you would find in areas such as Los Angeles, according to Kelley.

There is a strong regional flavor to retailing in the two Missouri metropolitan areas because, even with Walmart in nearby Arkansas and Kroger in Ohio, a chain based even closer to home dominates St. Louis.

The largest retailer in the St. Louis area, with 69 stores and 23 percent market share, is Schnuck’s Culinaria, which began during the Depression with a 1,000 square-foot outlet on the north side of the city and has grown to 100 stores in five Midwestern states. Straub’s, Save-A-Lot and Dierbergs are also major players.

Hy-Vee has grown over the past 88 years from its modest beginnings in the small store Charles Hyde and Vredenburg opened in Beaconsfield, IA, to become a regional chain with nearly 250 stores in eight Midwestern states, including 20 outlets in the greater Kansas City area.

St. Louis and Kansas City both have large numbers of consumers looking for value pricing as Walmart and Sam’s Club alone account for more than 28 percent of retail sales in both cities, according to the Chain Store Guide’s 2017 Grocery Market Share report.

There are more than 270 dollar stores of various brands in the St. Louis metropolitan area and another 190 in greater Kansas City.

But both markets are segmented, as there are adequate outlets for consumers who have the means and the desire to buy their produce at more premium outlets.

Save-A-Lot, Whole Foods, Sprouts and Trader Joe’s have significant presence in Kansas City, while Fresh Thyme, Trader Joe’s and Whole Foods combine for 10 stores in the greater St. Louis area.

There also were nearly 11,000 eating and drinking establishments in Missouri in 2015, according to the Missouri Restaurant Association, and they employ more than 300,000 people. The association expected employment to grow by nearly 10 percent over the next decade as the restaurant industry builds on a vibrant history.